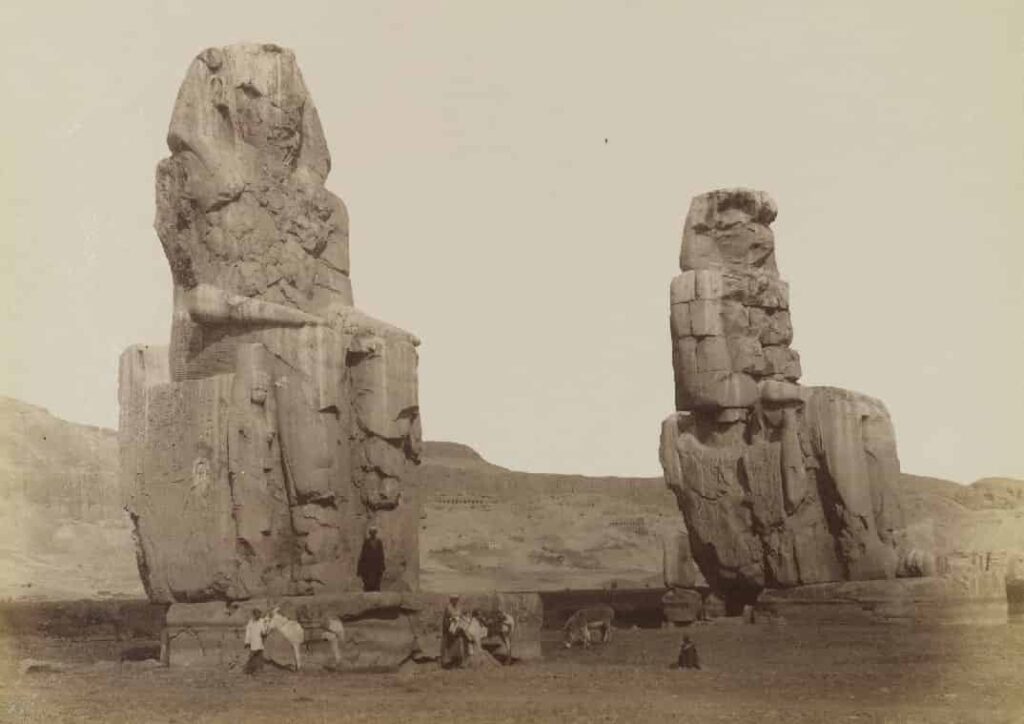

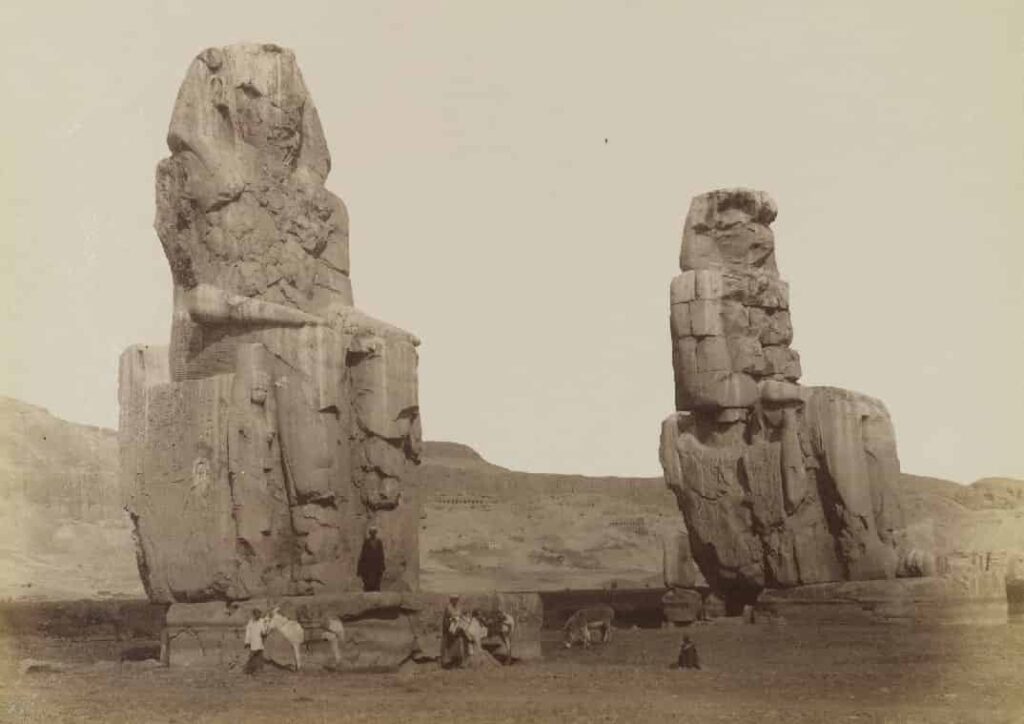

The entrance pylon of Amenhotep III‘s Temple of Millions of Years.

Forming part of the funerary temple of one of the greatest pharaohs of ancient Egypt, the colossi have their own history and legend, which has made them famous beyond the borders of the Two Lands.

The history of the colossi of Amenhotep III

Although they now appear fragmented, both colossi are sculptures made from a single block of quartzite, believed to have been extracted from the Gebel el-Ahmar quarries near Cairo (about 20 km north of ancient Memphis).

These impressive statues represent Amenhotep III himself, the ninth pharaoh of the eighteenth dynasty (who reigned ca. 1391-1353 BC). In ancient times, they marked the entry point of the monarch’s funerary temple, which stretched for almost 1km in length, starting at the first pylon behind the colossi.

The colossi, nearly 20 m high and about 1,000 T, show the monarch seated on a throne, with his arms on his legs, wearing the Neme headdress and skirt pleated.

Next to the legs of both Amenhotep III statues, we see the representation of several women in the north colossus. The one on the right appears to be Mutemwiya, the mother of the King. In the south, we see Amenhotep III accompanied by his wife, Tiye, and one of his daughters, whose name we do not know.

Two gods of the Nile are represented on the sides of the throne, uniting the symbols of Upper and Lower Egypt, the lotus and the papyrus, in what is known as Sema-Tawy, the union of the Two Lands.

The creation of the colossi is attributed to “Men”, who was the “chief sculptor of the great monument of the king on the red mountain”.

We have the colossi, but what happened to the Temple of Millions of Years of Amenhotep III?

The answer is easy: it is the largest funerary temple in Thebes, and for its construction, stone and adobe bricks were used for the most part.

This material, together with the fact that the temple was located in the floodplain, made the building. It had already begun to deteriorate in ancient times when it stopped receiving adequate attention. The waters that arrived with the flood of the Nile were slowly undoing the mud bricks with which the temple was built.

In addition to this, there was an earthquake in 1,200 BC that damaged the building.

After this earthquake, several monarchs after the great Amenhotep used the stones of his temple for their own constructions. We imagine that they were scattered around the enclosure after the earthquake.

And now we are faced with a new question: why build a temple in the flood zone? For pure symbology.

When building the temple here, it was intended that the Nile’s waters would reach it with the flood year after year. The entire temple, except for the sanctuary – which would have been built on a mound – would have been flooded during the flooding of the river.

This way, when the flood receded, the temple literally represented the emergence of the world, and life, among the primeval waters of creation (this is how the ancient Egyptians believed that the appearance of the world had taken place for the first time, with a mound of earth that arose between the waters of the Nun, the original ocean).

Now, we have to ask ourselves where the name of the colossi of Amenhotep III comes from since Memnon does not refer to any Egyptian story, but to Greek.

In addition to the earthquake of 1,200 BC, we know that there was a new earthquake in 27 BC in Thebes, recorded by the Greek geographer Strabo (64 BC – 21 AD).

The City and its temples suffered the consequences, as well as our colossi, particularly the northern colossus since, from this shake. The northern statue emitted some singular sounds.

Every morning, with the sunrise over the horizon, the northern colossus began to “groan”. This made quite a claim among Greek and Roman travelers, who believed that these “laments” brought good luck to anyone who heard them.

Thus, from this moment, many arrive in Thebes wanting to listen to the ancient Egyptian giant (currently, these sounds are attributed to the change in temperature and humidity suffered by the stones of the colossus at sunrise, which would make them emit these particular noises when the wind passed through its cracks at certain times).

And here the legend begins; due to these moans, the Greeks associated the northern colossus with the Greek Memnon.

The giant’s laments did not last long since, in the year 199 AD, the Roman emperor Septimius Severus wanted to fill in the gaps in the sculptures in an attempt to improve the appearance of the colossi.

This restoration caused the sounds to cease, forever silencing the “groans” that made the statues of Amenhotep III so famous, which, in their day, flanked the entrance to the largest and richest of all the mortuary temples of Thebes.