Rise From the Ashes

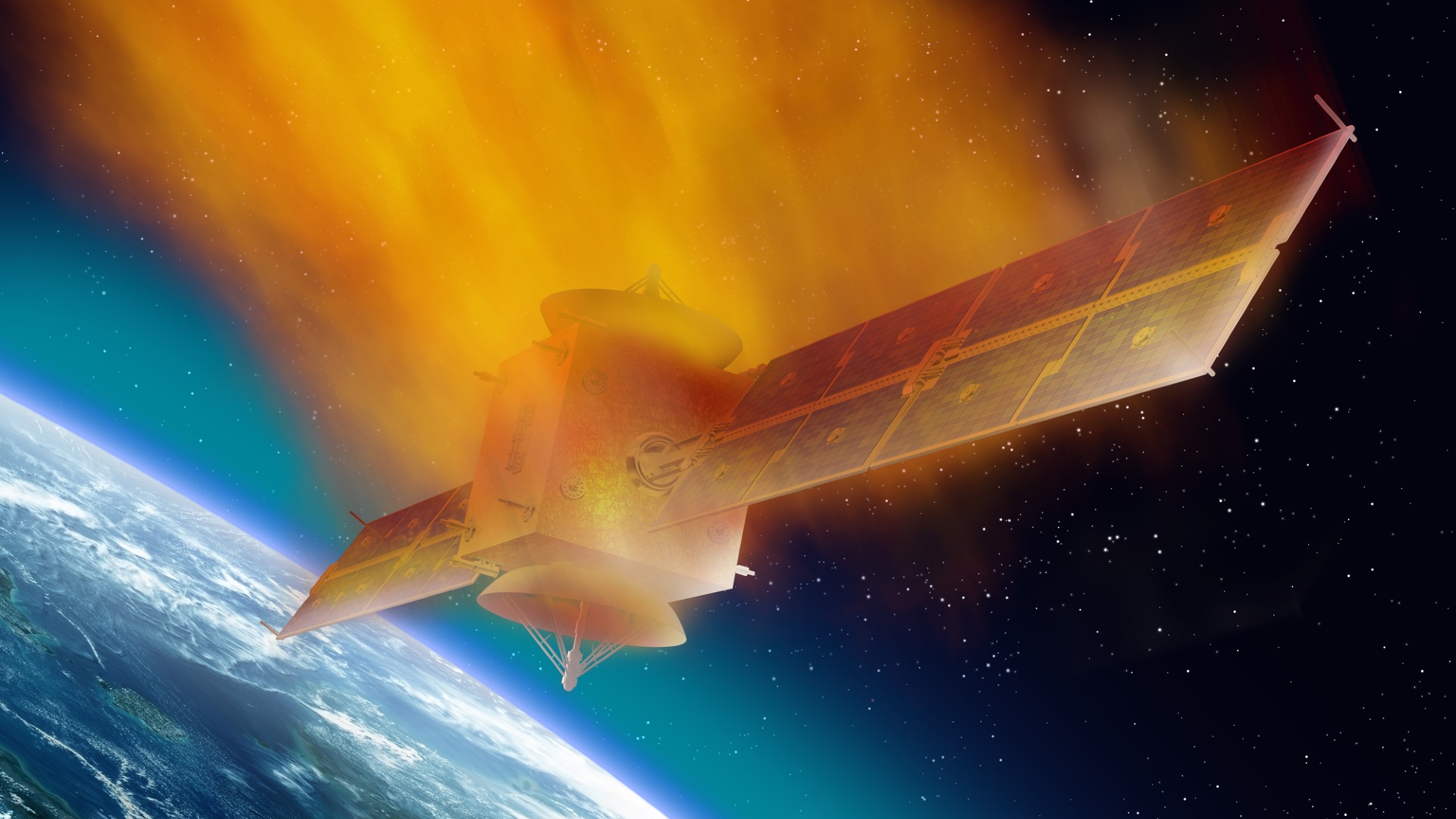

SpaceX’s massive constellation of satellites are an eye-grabbing spectacle, but they’re also the center of great controversy, ranging from concerns about space junk to astronomers complaining they’re blocking their observations of the sky.

Now, a contentious and yet-to-be-peer-reviewed paper has suggested an even more catastrophic consequence of the Starlink network. As its satellites and others burn up in our atmosphere, their magnetized “dust” could pollute our atmosphere and weaken our planet’s magnetic field, which extends thousands of miles into space and shields us from dangerous cosmic radiation.

“I was shocked at everything that I found and that nobody has been studying this,” the author, University of Iceland doctoral student Sierra Solter-Hunt, told Live Science in a new interview. “I think it’s really, really alarming.”

Genuine Particle

Solter-Hunt estimates that it’s possible that the amount of metallic particles in our atmosphere has increased by a millionfold since the start of the space age.

As more commercial satellites are launched and then burned up in the coming decades, that tally could reach a billion fold, she told Live Science, with most of the dead satellite dust accumulating in an upper region called the ionosphere that extends up to 400 miles above Earth — “and it could just stay there forever.”

This could form a “perfect conductive net around our planet” that if electrically charged, would block our protective geomagnetic field from extending past the ionosphere. In the “most extreme case,” the outer edges of our atmosphere, no longer fully protected by the geomagnetic field, would be stripped away by the harsh radiation of space over centuries.

Junk Science

Could the disintegrated remains of a few hundred thousand satellites really be enough to radically alter the Earth’s mighty magnetic field? Many experts are skeptical.

“Even at the densities [of spacecraft dust] discussed, a continuous conductive shell like a true magnetic shield is unlikely,” John Tarduno, a planetary scientist at the University of Rochester, told Live Science, calling some of the paper’s assumptions “too simple and unlikely to be correct.”

It’s also not clear if there will ever be that many satellites in orbit. SpaceX has launched nearly 6,000 so far, and Amazon plans to compete by eventually deploying over 3,200 satellites of its own — huge multi-billion dollar projects that nonetheless come nowhere near the tally of up to 1,000,000 that Solter-Hunt based her assumptions on.

Still, others argue there’s merit to the work. If nothing else, it underscores just how little we know about metallic pollution in our atmosphere, or how these satellites could affect the health of our planet.

“This is not an issue to be ignored,” Fionagh Thompson, a physicist at Durham University in England told Live Science. “There is a need to step back and view this [space junk pollution] as a completely new phenomenon.”