The unexpected find is way larger than any other known colony of fish nests found so far.

The fact that we know less about the ocean floor than we do about the surface of the Moon doesn’t make this incredible find any less surprising. Five hundred meters below the ice covering the south of Antarctica’s Weddell Sea, a research team recently discovered the world’s largest fish breeding site known to date.

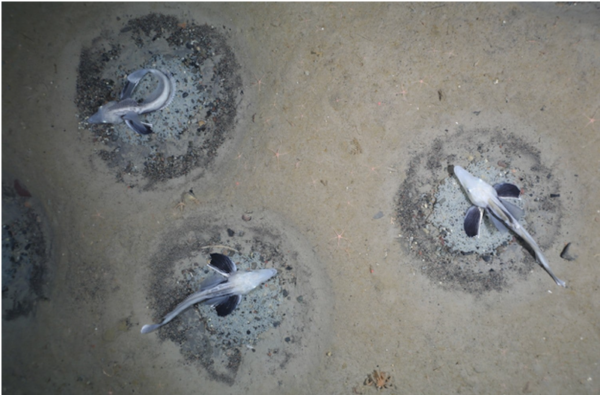

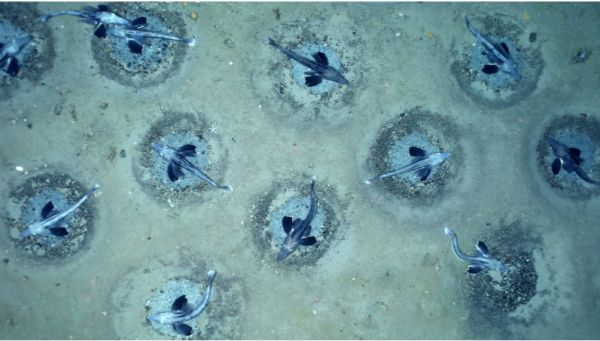

According to a new study published in, an estimated 60 million active nests of Jonah’s icefish (Neopagetopsis ionah) stretch across a vast area of at least 240 square kilometers. The discovery was facilitated by a towed camera system led by the German research vessel Polarstern.

Until now, researchers have encountered only a handful of icefish nests at a time, or perhaps several dozen. Even the most gregarious nest-building fish species were previously known to gather only in the hundreds (other such species include the artistically inclined pufferfish, and freshwater cichlids).

Deep sea biologist Autun Purser of the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven, Germany, and colleagues stumbled across the massive colony in early 2021 while on a research cruise in the Weddell Sea, which is located between the Antarctic Peninsula and the main continent.

According to their findings, the icefish probably have a substantial and previously unknown influence on Antarctic food webs.

Icefish are special not only due to them being the only known vertebrates that lack red blood cells containing hemoglobin (hence the name white-blooded icefish), but also because they have a protein-based antifreeze in their blood (white in color and nearly see-through, by the way) which makes life for them under the Antarctic ice shelf feasible. So much so, that the nesting ground discovered by the researchers is as big as the Island of Malta, with one breeding site per 3 square meters (32.3 square feet).

Estimates from the Polarstern‘s observations put the number of nests at the nesting ground at around 60 million, demonstrating that the area is a vital one for the species and a marine environment worthy of protection. A proposal to establish a Marine Protected Area here has been under consideration since 2016 by the European Union and the international Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), but unfortunately it hasn’t happened yet.

“The idea that such a huge breeding area of icefish in the Weddell Sea was previously undiscovered is totally fascinating,” said Purser, lead author of the study, in

Purser’s enthusiastic statement is easy to understand when you realize that the AWI has been researching this particular stretch of the Weddell Sea for the past 40 years, but so far only small clusters of icefish breeding sites were found. So, why exactly here? The team used oceanographic and biological data to establish that the vast breeding site coincided with an inflow of warmer deep water from the Weddell Sea onto the nesting ground shelf.

Since each active nest contains about 1,000-2,000 eggs and there are many adults hanging around to protect them, the biomass of the colony is estimated to weigh around 60,000 tons. It is now wonder, then, that the resource-rich area is also frequented by hungry Weddell seals.

Being the most spatially extensive contiguous fish breeding colony ever recorded on Earth, the nesting site definitely tops the charts for significant breeding sites – a pretty solid argument for the establishment of the marine protected area proposed.

“Considering how little known the Antarctic Weddell Sea is, this underlines all the more the need of international efforts to establish a Marine Protected Area (MPA),” said AWI Director and deep-sea biologist Professor Antje Boetius, who took part in developing non-invasive technology that to allowed the team to observe the ecosystem without disturbing it. “Unfortunately, the Weddell Sea MPA has still not yet been adopted unanimously by CCAMLR. But now that the location of this extraordinary breeding colony is known, Germany and other CCAMLR members should ensure that no fishing and only non-invasive research takes place there in future.”

ÚLTIMAS NOTICIAS: Kanye West guarda silencio sobre los rumores de “incesto” — pero esta acción lo dice todo… y deja a todos perplejos Los Ángeles –…

ÚLTIMAS NOTICIAS: Kanye West guarda silencio sobre los rumores de “incesto” — pero esta acción lo dice todo… y deja a todos perplejos Los Ángeles –…

ÚLTIMA HORA: Podría perder el apoyo de Trump… pero FOX tiene otros planes aterradores que podrían cambiarlo todo Washington D.C. / Nueva York – Abril 2025…

ÚLTIMA HORA: Podría perder el apoyo de Trump… pero FOX tiene otros planes aterradores que podrían cambiarlo todo Washington D.C. / Nueva York – Abril 2025…