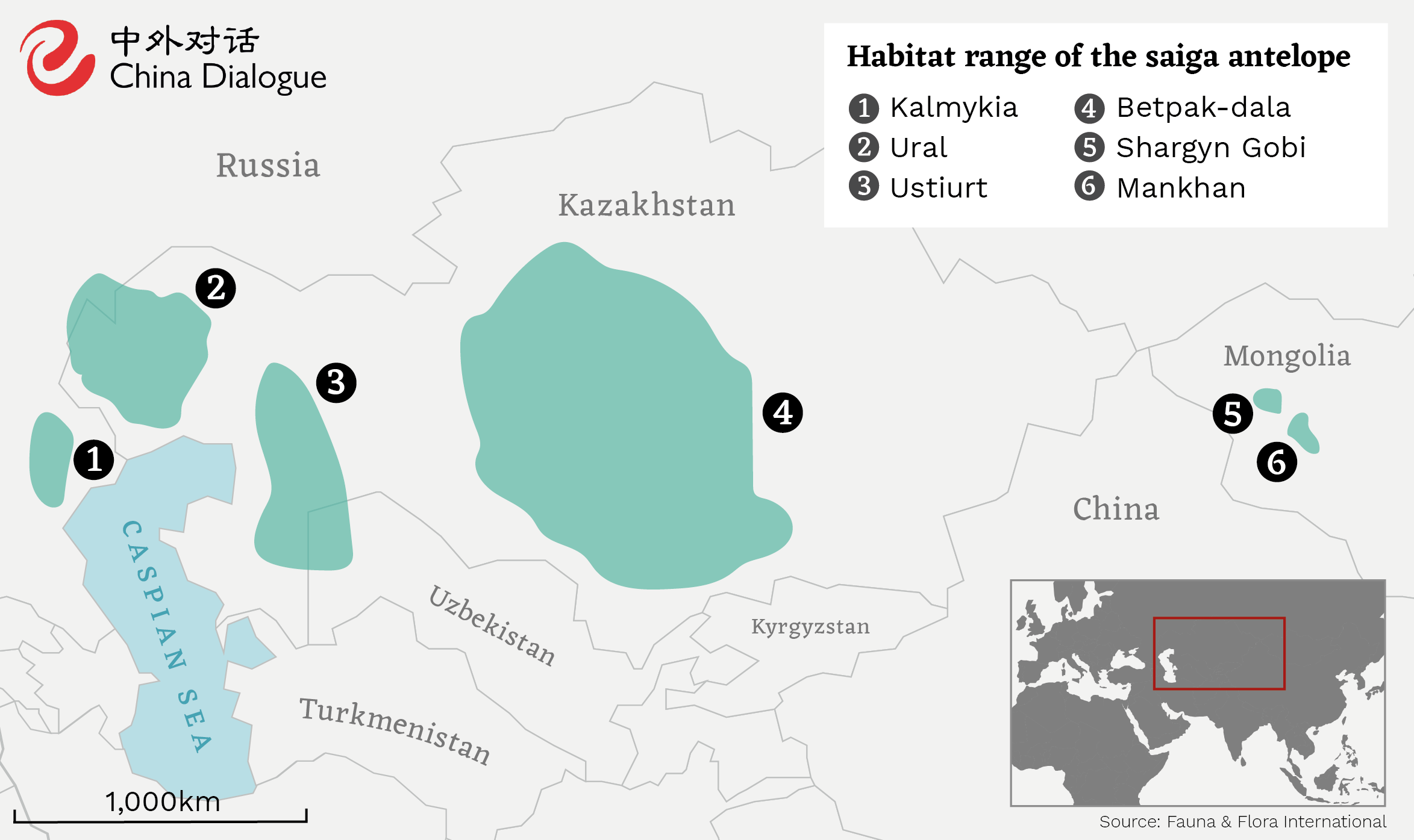

Saiga antelopes once migrated with woolly rhinoceros and mammoths across vast territories from the British Isles to Alaska. Between 45,000 and 10,000 years ago, they were widespread in the northern hemisphere. Now, the species’ range is mainly limited to the grasslands and deserts of Kazakhstan, and parts of Uzbekistan, Russia and Mongolia.

Known for its trunk-like nose, the saiga is classified as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) . However, most people only heard of it in May 2015, when more than 200,000 people died suddenly and mysteriously in three weeks in Betpak-Dala, central Kazakhstan.

In 2018, the number of adult saigas was around 125,000, down from more than 1 million in the 1990s.

Signs of recovery

Conservationists report that saiga populations in Kazakhstan and Russia doubled in 2019, to about 300,000 individuals. This number is predicted to reach 500,000 in the next two years.

Munib Khanyari, a researcher at the University of Oxford’s Center for Interdisciplinary Conservation, said the saiga’s recent recovery “is largely due to the great efforts of NGOs such as the Diversity Conservation Society.” Kazakh Biodiversity, government agencies such as Okhotzooprom [Kazakhstan wildlife protection agency], and park rangers, who raise awareness, conduct patrols and limit activities poaching. This is not to say poaching doesn’t exist – it does and is always considered in conservation plans.”

Conservationists are also cautiously optimistic following reports in June of a mass herd of calves in the Ustiurt Plateau population in Mangystau, Kazakhstan. The birth of 530 calves doubled the population in that area in 2018.

Male Saiga with rutted wheel tracks (Image: Saiga Conservation Alliance )

The saiga are resilient, and given the opportunity, their population growth rate could be high, the researchers say.

“The discovery of a mass herd of calves in the Mangystau region is really a positive sign,” said Khanyari. “This population is known to migrate south to parts of Uzbekistan in winter, but is affected by infrastructure projects such as railways and fences built around the Kazakh-Uzbek border. It is important to monitor this population to see how it responds to these infrastructure challenges.”

Poaching has not been eliminated

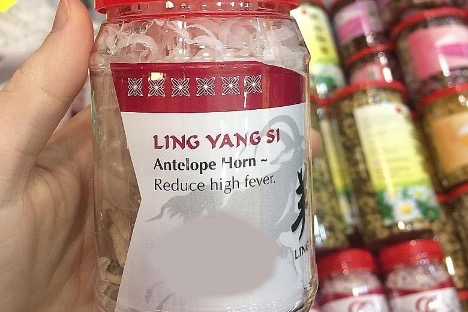

Poaching for antelope’s horns and meat, which increased sharply in the 1990s, continues to threaten the species. Horn is used in many traditional Chinese medicines, as it is said to treat fever and sore throat.

Saiga horns for sale (Photo: Andrey Gliov & Karina Karenin, The New Paper )

After China, Singapore is the largest importer and consumer of saiga . In both countries, horn and its derivatives are legally traded and consumed. Research shows that 1 in 5 Chinese Singaporeans use medicinal products derived from saiga horn, commonly known as ling yang .

The need for drugs is not the only threat. In September 2019, researchers concluded that “the rapid increase in poaching is in fact a direct result of the collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent loss of administrative and law enforcement in the states covered by the saiga, as well as widespread rural poverty.

“I think poaching is not nearly at the level it reached after the collapse of the Soviet Union,” says Khanyari. “Soon [that] people almost overnight lost institutional support for raising livestock, and started killing saiga for meat and also males for horns. Selective harvesting of males [hornless females] leads to population collapse, as saiga are harem-breeding species [one male mates with many females].”

Boiled saiga meat in 2009 (Photo: Saiga Resource Center)

According to Orazbay Abdirakhmanov, who has written a number of books on the environmental challenges in the Aral Sea region, multiple factors caused the population to drop. These include uncontrolled poaching, physical borders negatively affecting migratory species and loss of habitat to industrial projects, such as oil and gas pipelines and railroads after 1990.

Impact of climate change

Scientists have identified another worrying cause of the species’ decline: climate-related and environmental stressors, which may exacerbate existing challenges. Research from British conservationists Richard Kock and Eleanor Milner-Gulland has linked mass-mortality events with high levels of humidity. “Most die-offs occur at a mean average maximum daily relative humidity of more than 80%,” they wrote in a recent paper. “In May 2015, atmospheric moisture was extreme with some of the highest recorded values for that time of year since 1948.”

Did you know?

The saiga’s unusual nose filters dust, cools summer air, warms winter air and attracts mates.

Khanyari said: “Mass die-off is going to be a concern over the coming years. It is key our conservation efforts ensure that saiga populations grow big enough to deal with these catastrophic but often natural events.”

“There is evidence that the 2015 mass die-off, like a few in the past, was related to Pasteurellosis, an infection caused by the bacteria pasteurella multocida and driven by climate anomalies. This bacteria usually lives in the oesophagus of antelope, but because of the temperature/humidity anomaly during the calving time (when females are already physiologically stressed), this bacteria turned virulent and caused haemorrhagic septicaemia. While that is the proximate cause, the ultimate cause remains unknown.”

Potential human conflict

While the recent growth of the saiga population is good news for biodiversity, farmers might see things differently. Local news sources reported farmers in north-west Kazakhstan suffering losses after herds of the Ural saiga population migrated through their crop fields.

A saiga herd (Image: Munib Khanyari)

“The government agencies and NGOs, from my knowledge are still gathering baseline data/evidence of this occurrence to then provide evidence-based interventions (if necessary),” said Khanyari. “I think it will be key for various stakeholders to work together towards a land-sharing rather than land-sparing way to conserve saigas. Historically, huge numbers of saiga shared the steppe with huge numbers of livestock, so it can be done.”

He added: “Overgrazing might be a concern as saiga numbers increase, but it is important to contextualise this within the bigger picture. Climate change is impacting these lands in various ways and also livestock numbers are rebounding after the dip following the Soviet break-up.”

Protecting Central Asia’s ‘natural heritage’

The government of Kazakhstan has stepped up its efforts to eradicate poaching by criminal organisations – which claimed the lives of two park rangers in 2019. Last year, the country’s National Security Committee conducted a nationwide operation, seizing over a tonne of saiga horns destined for China, with an estimated value of more than US$14 million.

The country’s president Kassym-Jomart Tokayev said: “Poachers keep on hunting saigas, our natural heritage. They must be severely punished in accordance with law.”

Conservationists and scientists say a multi-disciplinary approach is necessary, together with inter-state protection of the endangered species from illegal poaching. There must also be routine monitoring and research, so that countries in the region are better prepared for disease outbreaks.

Researchers weigh a saiga calf (Image: Munib Khanyari)

“Saiga are critical for the ecosystem of the region. As the primary consumer, they impact processes such as vegetation composition and nutrient cycling. Without the saiga the steppe ecosystem will likely be negatively affected, which has the potential to affect local water supplies and the climate. Saiga are also food for predators like wolves and even steppe eagles, so play a critical role in the food chain,” said Munib Khanyari.

“Beyond this,” he added, “saiga are extremely important culturally and historically. Saiga have been roaming the Earth since the time of species like mammoths. They are like living fossils.”

“Eu nunca tinha me sentido assim em cena” – Blake Lively revela tensão real em discussão acalorada com Henry Golding no set de Um Pequeno Favor…

“Eu nunca tinha me sentido assim em cena” – Blake Lively revela tensão real em discussão acalorada com Henry Golding no set de Um Pequeno Favor…

BREAKING NEWS: Trump’s Career in Peril After Explosive Leak—Experts Warn “This Could Be the Beginning of the End” In a political earthquake that has sent shockwaves…

BREAKING NEWS: Trump’s Career in Peril After Explosive Leak—Experts Warn “This Could Be the Beginning of the End” In a political earthquake that has sent shockwaves…

ÚLTIMA HORA: Michael Douglas y Catherine Zeta-Jones Confirman que Están Divorciados, Pero lo que Sorprendió a Todos Fue… En un giro inesperado que ha dejado boquiabiertos…

ÚLTIMA HORA: Michael Douglas y Catherine Zeta-Jones Confirman que Están Divorciados, Pero lo que Sorprendió a Todos Fue… En un giro inesperado que ha dejado boquiabiertos…

SHOCK: El Impactante Caso del Testigo de Jimmy Hoffa – Una Nueva Declaración Sacude al Público Una nueva vuelta de tuerca sacude uno de los casos…

SHOCK: El Impactante Caso del Testigo de Jimmy Hoffa – Una Nueva Declaración Sacude al Público Una nueva vuelta de tuerca sacude uno de los casos…

NEWS UPDATE: Angelina Jolie, 49, Faces “Empty Nest Syndrome” as One of Her Children Moves Out — A Bittersweet Turning Point for the Devoted Mother Angelina…

NEWS UPDATE: Angelina Jolie, 49, Faces “Empty Nest Syndrome” as One of Her Children Moves Out — A Bittersweet Turning Point for the Devoted Mother Angelina…

ÚLTIMA HORA: La industria del alquiler de úteros — Las fábricas de bebés en China explotan el derecho de ciudadanía por nacimiento y confirman nuestras peores…

ÚLTIMA HORA: La industria del alquiler de úteros — Las fábricas de bebés en China explotan el derecho de ciudadanía por nacimiento y confirman nuestras peores…